Lankelly empowered many people to challenge the status quo

That battle goes on—but now we’ve lost a valued advocate and vital resources too

A Lankelly Legacy Interview. Hosted by Generative Journalism Alliance

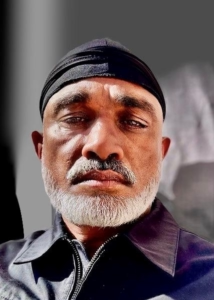

Sohan, what was made possible through your work with Lankelly that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise?

I think the relationship we’ve had with Lankelly Chase as an ethnic minority organisation has been one that we’ve truly valued. It’s been a relationship built on honesty and trust—something we’ve never experienced with any other organisation or institution before.

Because of that, we were able to engage openly, without holding anything back—whether it was about our situation as an organisation, the issues affecting the community, or our experiences with local authorities.

We first connected in 2016, and in 2017 we worked together on a piece of community action research. That research was published in 2018 and became a very powerful document—almost like a ‘passport’ to challenge the system.

The work we did with Lankelly Chase put us in a much stronger and more powerful position. On our own, we would likely still be struggling, and the pushback from the system would have been much greater.

The report, Cultural Connection and Belonging, truly challenged the status quo of the UK’s approach to severe and multiple disadvantages. That approach has historically been based on Caucasian, Anglo and Eurocentric thinking and experiences. We brought a different dimension to the conversation, and that sparked interest because it was new. There was genuine interest from the wider society and the health sector.

What social shifts have you witnessed?

Over time, others began to support our stance. We made it clear that issues regarding ethnic minorities—mistrust of services, lack of engagement—weren’t just our problems to address. These were collective issues, and everyone around the table needed to own them. We turned the tables, shifting the narrative, and confidently argued that these were problems we all needed to speak about and solve together. We called on others to support us, as we were tired of being the single voice, demonised and ostracised for speaking out.

What we’ve done is build an alliance of other voices. Now, academics, commissioners and others speak about the same issues we’ve been raising for years. This increased visibility and interest has been amplified thanks to our relationship with Lankelly Chase. They’ve played a key role in enabling us to elevate these conversations and drive meaningful change.

What meaning was made for you through that experience? Was there anything that surprised you and did you have any key takeaways?

Nothing really surprised me. I’m a believer that if you have an honest and transparent conversation—a real conversation—you can sense the truth. Engagement, when founded on truth and honesty, feels different.

What I’ve taken away from Lankelly Chase is the importance of not shying away from speaking your truth, but also not hesitating to ask for honest conversations.

We feel that we were stronger with Lankelly Chase. Our voices were heard. It’s almost like we’re being kind of left in the lurch now, especially with our local authorities in Nottingham, and with commissioners—the power and oppression have started. Before, they were a little bit lax because they knew that we had a big foundation alongside us.

So how are you feeling then about Lankelly’s decision to wind down its current structure?

I understand their values and principles, which I’m completely on board with.

We’ve been speaking to foundations for the last quarter of a century. Even the Big Lottery as an organisation—they don’t fully understand the extent of the issue, but have been supporting our efforts, how much the system needs to change, how much more work needs to be done.

The work on justice, equity and inclusion for us still goes on. It’s still a battle. But where we’re struggling is around funding. Around local authority funding, for example—the system didn’t change. What they’ve done is they’ve become more resourceful in their tokenising techniques. Right now, at the moment, they’re just tick-boxing.

What would you like to see now from the wider philanthropic field?

What Lankelly Chase helped us to do was to fine-tune our culturally-informed recovery model. That model can work across mental health, criminal justice—it can work across sectors. It’s about how we can be supported in articulating that and getting it out there, so other organisations can benefit and we can begin to find sustainable solutions for the ethnic minority population in the UK—even in Europe, where problems around addiction, recovery and treatment are really bad.

We would like that support to help us market ourselves, and also support us as a growing organisation. We’re limited in terms of how many people we can see, when in reality we could see so many more. We haven’t got the space we need to hold large training sessions, open spaces, drop-in spaces or even spaces for staff and one-to-one meetings.

We are people from the communities, running this collectively together. But we need resources for that to happen. We need property, we need land, we need accommodation. We’re capable of doing the work—we’ve got the solution, we’ve got the drive, we’ve got the skills and we’ve got the knowledge. But what’s missing is the funding, the resources, the money.

We’ve had conversations with healthcare providers in Canada and America, because people are hearing about our model. It would be a real shame if we couldn’t sustain ourselves due to a lack of resources and end up like other organisations that have gone under. We are trying to sustain ourselves through specialist training and consultancy, but we can only do so much. We need more staff, more professionals and recovery champions to help expand what we do. Right now, we’re just exhausted. Our team has gone from 15 full-time staff and maybe two dozen passionate, active volunteers down to six people.

Yeah, I hear you Sohan. What’s the best thing that could happen?

I’m a firm believer in introductions. When you introduce people to one another, doors open. But if we don’t know who we need to be introduced to, then we’re just doing what we’ve always done. And that’s part of the struggle, really.

That’s what needs to happen. We need to be involved. We need to step out of this world of commissioning and local funding competitions. We need different types of partnerships, and we’ll take it from there. Our work will speak for itself. The full depth and richness of the challenges we’re addressing, the changes required, and the support needed are all clearly laid out.

We’ve been introduced to some leading academics including Substance Use Treatment and Recovery advocacy organisations like CLERO (College of Lived Experience Recovery Organisations) and RGUK (Recovery Group UK) founded by the late Noreen Oliver MBE, CEO of BAC O’ Connor Centre, and we’ve built strong relationships with them. This is the kind of door-opening we need to see more of.

The solution is going to come from the communities—not the system. Local authorities aren’t going to provide the resources we need for sustainable change. They might fund temporary change and tick a box to say, “Look what we’re doing, we’ve ticked the DEI box here.” That’s been happening for the last 30 years.

We have so much to offer, but we need to meet people who can help us take our message to the next level. We’ve been regional for years. Let’s make it national. Let’s make it international.

We at BAC-IN, don’t want anything for ourselves. We just want to share what we’ve learned with communities, wherever the problems and issues are.

We want to help them develop their own recovery and rehabilitation solutions, mentor them, get them on their way, and then move on to the next city to do the same. We want to share our learning, knowledge and expertise, get a team together and make it happen.

Hosted by Tchiyiwe Chihana. Edited by Sam Walby

Learn more about Generative Journalism Alliance