Shifting how people relate to each other

Learning from community-led Systemic Action Research in Gateshead

By Jo Howard

What we’re learning is that shifting how people relate to each other is a very long, complex thing to try to do.

I think it’s a 10 year process to establish some different ways of working that are going to make a difference to people in communities. That’s what Lankelly were doing, and that’s what I would like to see other resource holders contribute to.

Shifting how people relate to each other

Lankelly Chase first approached myself and my colleague, Danny Burns, as people who were working towards systems change. We were doing that kind of work – building capacity, knowledge and action towards systems change with groups experiencing marginalisation.

They stood out as a very different kind of funder, who wasn’t trying to fund things with quantifiable, short term results. Lankelly understood that you’re contributing to something that’s much more complex. Trying to understand how change happens in systems, so that systems of oppression are shifted, requires long term and flexible ways of working.

When we first started talking in 2018 we had a few interesting conversations, which developed into the work in Gateshead in 2019. We had identified seven community organisations working with particularly marginalised groups in those neighbourhoods, and developed a process with Lankelly we call Systemic Action Research.

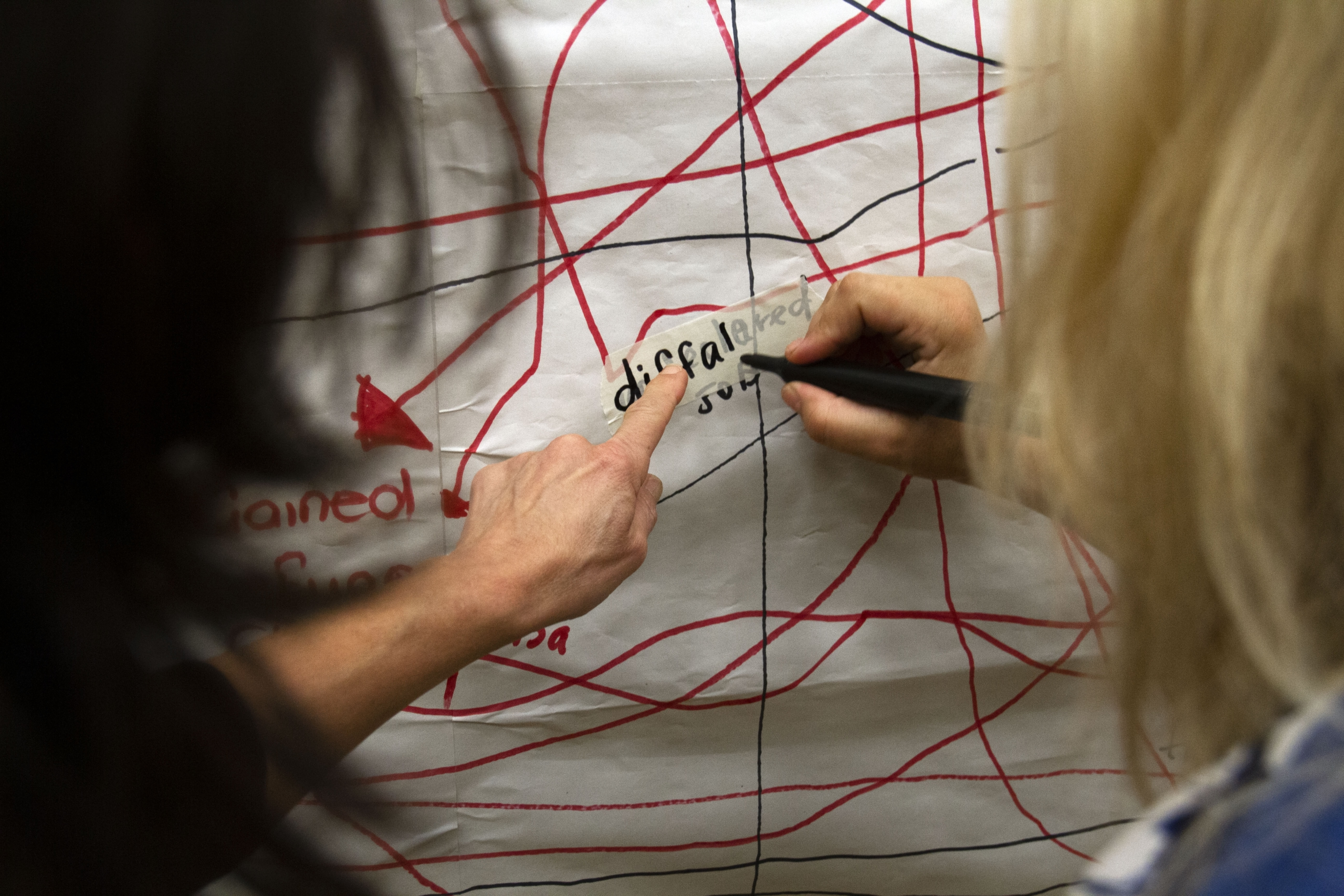

A core part of that is about shifting relationships. What do you mean when you’re going to change the system? What are the things that actually need to change? What we’re learning is that it’s about shifting how people relate to each other, and that is a very long, complex thing to try to do.

The shorter term things that change are – at least in Gateshead – by bringing together community members of marginalised communities, training them and working with them as peer community researchers builds their confidence. Then they also work together in different ways.

Something really remarkable in Gateshead – which made it more difficult, but richer in the long term – was that these community organisations all work with very different constituencies who probably wouldn’t normally talk to each other – refugees and asylum seekers alongside young, White British mums and dads, alongside people in recovery from addiction or experiencing mental health issues. By coming together, working together and trying to recognise shared issues, they were building new and different relationships with others within and across communities. That slow building of confidence and skills happens through those processes.

A real achievement of the way they’re working in Gateshead is that they’ve found ways of networking what they do through Bridge Builders, who are building bridges between different communities. I guess we’d call it ‘horizontal scaling out’, where you build relationships and different ways of seeing and talking to people.

It’s grown and continues to grow in Gateshead.

Importance of people in place

My sense is that, in Gateshead, because they had somebody in place who held the work and was there to support people, to talk things through, to listen to people, to explain and mediate things, that has worked.

Richard Gibbons has played quite an amazing role in holding things together. He held the groups and the community – the life of the work – the people doing that bridge building and the peer engagement keeping the groups going – that’s been invaluable. For example, the reason that somebody ended up joining one of the action research groups is because Rich went to their house and got them, took them to the bus and went on the bus with them to the meeting. That kind of thing! It’s the tiny – well, not tiny – rather momentous detail of the real stuff.

Give time to processes

The process has been a very difficult thing to navigate. In wanting to devolve decision making to people in community, there’s a transition when people are used to a way of working where it’s the funder who calls the shots, and then the funder says, ‘No, we don’t want to call the shots’, but they still hold the money. That has caused tension. Sometimes it’s felt a bit disingenuous of Lankelly to say, ‘Oh, but no, we don’t make the decisions’. But you do, because you have the money.

At the same time, I think what Lankelly has tried to do is remarkable. Most remarkable from a research perspective is that they invited and funded an open-ended action research process with communities. They didn’t want reports and indicators or logframes. They were happy to review and then fund a second phase, and they completely get that you can’t know where something’s going, that the nature of action research is that as it unfolds, it will take the direction that it takes. I would recommend other funders to follow that model.

It’s rare to have support for processes that can’t say upfront what they’re going to produce, and are looking at how to shift systems.

So give time to processes. Don’t expect change to happen in six months or a year. You’re contributing to processes that need to develop over the long term.

It also really makes a difference if you’re paying community researchers a living wage to do the work that they’re doing. I think that is transformative. It’s taking people’s time and knowledge seriously, and that’s been the absolute core of what Lankelly does and how they work.

Where to start?

I believe the place to start is with people experiencing marginalisation in their daily lives – building recognition, starting from that knowledge, building their confidence and capacity to communicate into other spaces.

I also wonder if funders like Lankelly could be looking at how they can shift the mindsets of those who hold resources and make decisions on behalf of those communities.

I also wonder if funders like Lankelly could be looking at how they can shift the mindsets of those who hold resources and make decisions on behalf of those communities.

I think the idea is that by building networks, confidence and actions in communities that are contributing to change, then others will start to notice and want to support those. I’m wondering if it would be useful to start involving those others more in conversations. It’s not like it’s an equation with the two sides, but part of the challenge in shifting systems is involving those other actors as well.

It’s a really difficult thing to do, trying to be a different kind of funder in a world that’s used to things being a certain way. So it’s brave to have those conversations and try to shift how we think about resources and resource holders.

In a similar way to participatory grant making, if you shift who makes decisions about spending money, that’s shifting a huge amount of power.

Story Weaving by Jack Becher

Learn more about Generative Journalism Alliance