What began in 2018 as an action inquiry into how to ‘build the field of systems change‘ became a journey into how the foundation could become a movement accomplice.

By 2022, we had a multi-stranded movements solidarity strategy in place.

This was developed by new team members with long term involvement, significant expertise and extensive networks in the movements space. Their insights greatly strengthened Lankelly’s ability to do this work, and we couldn’t have attempted it without this level of institutional muscle.

The global context of 2019-2020 dramatically affected the development of our work – from the impact of the covid pandemic to the conversations around racial justice and inequity. This created a sense of both urgency and real possibility.

During this time we saw the potential of movements for change, transformation and disruption. Change was happening inside Lankelly Chase too. By 2020 we were describing our role as creating the conditions “to tackle systems of injustice and oppression that result in the mental distress, violence and destitution experienced by people subject to marginalisation in the UK”. We had left the limiting framework of ‘severe and multiple disadvantage‘ behind us.

This meant the organisation was more receptive to an analysis which valued anti-oppression movements as well as (or even instead of?) the arguably rather rarefied, white-led intellectualism of the world of systems change.

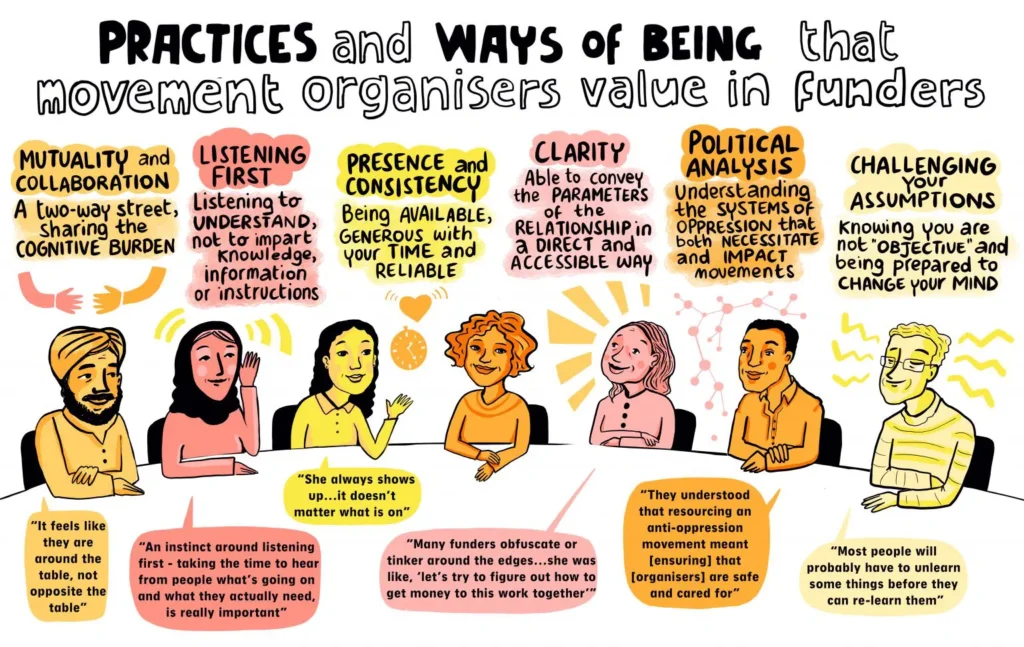

We began to explore how movements were resourced, nurtured and supported, aware that such work can be marginalised by institutional philanthropy because it doesn’t fit dominant, de-politicised understandings of what social justice work should look like.

We started to move money in accordance with the movement solidarity strategy.

In contrast with some of Lankelly’s prior modes of operating, which saw us working in the field with the people we were funding, the movements work focused on shifting money quickly and at scale.

Aware that movements have been most successful when ideas, tactics and strategies have cross-pollinated beyond imagined or imposed borders, this work included an international element. For example, we funded War on Want to work with other movement regranters to move £2m to movements across the globe over 2024-2026.

The transition pathway decision was made before the strategy was fully executed and somewhat cut across it.

There is a detailed account of the work we did and the organisations we supported here.

Lankelly was already changing (for example, through the recruitment of new trustees) but this work changed us further.

It meant we engaged with many new grantees with a sophisticated internationalist, intersectional, solidarity-based and explicitly anti-oppressive analysis, and a set of practices to match.

In the past, the impetus for Lankelly’s work had largely come from the staff team who, by dint of their experience in the world of charities and government, could claim some level of expertise in the field of severe and multiple disadvantage. This new work was outside the experience of many colleagues, and apart from a couple of experts who were recruited to lead it, we were all novices. This meant we could not relate to it in our usual way. We were educated and disrupted by it.

Along with the growing, worrying feelings about the dissonance between who were were as an institution and what we were trying to do, this was one of the factors which led to the transition pathway decision.

Related stories

-

Building an economy rooted in care and liberation

We need a movement infrastructure in which funders are the organisers themselves.

Guppi and Noni, Decolonising Economics Read more -

Lankelly were looking for rough diamonds to polish

Lankelly Chase’s closure is bold and necessary, but will it be a beacon to the rest of the philanthropic sector?

Yvonne… Read more -

Seed funding for early work uncommon

Lankelly shouldn’t be exceptional, but it is.

Mandy Van Deven, Elemental Read more