Until 2018, Lankelly’s approach to its investments was conventional.

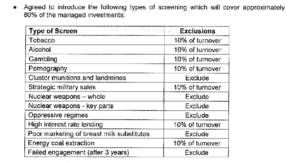

There was a nod to ethical investment through the exclusion of certain companies, such as arms manufacturers, but the purpose was solely to make money for the foundation to disperse in grants for as long as possible.

(From our 2014-15 annual report)

Governance of the endowment was delegated to the Investment Committee, whose members were often selected for their investments expertise. It was quite separate from the rest of the organisation’s work, and from the mission.

This was – is? – common across the foundation sector, with endowments being seen as the ‘goose which lays the golden egg’. Staff concerned with mission-related work, even CEOs, were often discouraged from interfering.

As Lankelly’s systemic approach in its mission-related work developed – in particular, the idea that the foundation was part of the systems it sought to change – questions about what the investments were doing in the world came up.

Membership of the Investment Committee evolved to include more trustees without investments expertise and questions were raised about how our investments could make a broader contribution to the mission, rather than just making money for the mission.

There was also a growing recognition that the wider financial system could be working against the goals of the foundation. As an actor with a foothold in that system through our investments, we saw an opportunity to shift it. We felt a sense of responsibility and a desire for integrity and alignment with our mission-focused activity.

In 2019, we appointed our first investment director, with a brief to explore whether the foundation’s investment capital could be doing more to support the mission.

This was against a backdrop of an awakening across the philanthropic sector in relation to climate change. The Association of Charitable Foundations’ 2019 conference was on that theme, and foundation endowments were described the ‘£68 billion elephant in the room’.

The first step for Lankelly was to divest from fossil fuel companies in the investment portfolio.

This was not uncontroversial in the organisation; some trustees raised concerns about the potential impact on returns, as well as whether it would achieve anything more than virtue signalling. On the flip side, the investment case for holding these stocks was fundamentally at odds with our organisational vision, and we found no evidence to persuade us that ‘shareholder engagement’ could lead to a sufficient transformation of companies’ business models. We were starting to make more grants for climate justice work, and the argument that we would be positioning ourselves in solidarity with the wider movement to withhold capital from fossil fuel production won the day.

The staff supported this move, in part because it helped provide more mission-aligned answers to questions from grantees about the sources of Lankelly’s wealth. We had introduced the idea of ‘mutual due diligence’ and we could now answer these questions in a way which (at least partially) reassured grantees.

We talked about divestment with our fund managers, which quickly revealed a misalignment with them.

While our managers were willing to exclude fossil fuel producers from our portfolios, we realised their presence was a symptom of a deeper problem. These strategies were predicated on, and designed to profit from, what we considered to be an unsustainable and untenable status quo. Simply removing fossil fuel producers wouldn’t resolve this tension; among our next largest investments were banks providing substantial financing to the very same fossil fuel producers.

In one conversation, we were told ‘we understand where you are coming from, however, you appointed us for a reason and this is how we do things. We can take fossil fuels out of the portfolio, but we’re going to end up having to replace them with something you’re probably not going to be comfortable with either. So maybe we’re not the best partner for you’.

We also realised how many layers there were between us and where the money was actually at work. We couldn’t see everything that we were invested in due to the ‘fund of funds’ structure of our portfolio.

An example of this was during the early days of the COVID pandemic. There was a lot of volatility within financial markets but one of our portfolios stood out as doing surprisingly well. When we looked into it, we realised that it contained a third-party fund which was effectively betting against companies and economic stress. Everything was in meltdown and we were making ‘good’ money because of it. That was a real wake-up call.

We felt we would have to interfere to an increasing extent in individual capital allocation decisions to get the results we wanted – in effect doing the fund managers’ jobs for them and ultimately trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. This didn’t feel right.

We were also frustrated that the segregated account, ‘fund of funds’, structure of our portfolio meant we couldn’t get to meet the people making the actual investment decisions. We would interface with a ‘client director’ whose job it was to manage us, smooth things over and present a certain kind of spin on how things were being done, such as talking up sustainability considerations.

We decided to look for new investment managers who were closer to us in terms of how they saw the world.

We focused initially on the equities portion of Lankelly’s portfolio (about 70%), which the Board had identified as the cornerstone for its long-term goals. We earmarked the remaining 30% for more diversified and alternative investments, potentially including community-based assets with greater transformative potential.

We also shifted from the typical structure which many charities use, and which we had used in the past; a multi-asset manager investing in lots of underlying funds. We wanted to be able to talk directly to, and understand the thought processes and values of, the people making the decisions.

What had started as divestment from fossil fuels broadened to the whole way we were relating to the investment system. We wanted much less separation, much less distance. We wanted to be more in relationship with the individuals making decisions and acting on our behalf, and we wanted to enter into that relationship from a position of alignment.

We agreed Statements of Intent with our new fund managers with the intention of working with them in more of a partnership – mirroring some of the relational approaches in our grant-making. We invested in pooled funds which already had an asset based of investors bought into the same investment philosophy.

We wanted to see what was made possible by working together, including collaborating on issues relating to our grant priorities with input from our funded partners, like ‘green extractivism’ in the supply chains of electric vehicles.

We also changed how the Investment Committee worked. We had new policies and frameworks geared towards embedding this kind of more integrated, congruent, holistic approach, including monitoring and evaluation. One example was that previously we had started every meeting looking at financial performance over the prior three months. We realised how much that had anchored us in a very narrow and short-term perspective.

We were pleased to be stepping into closer partnership with our new investment managers. We felt they were much more aligned and the conversations were much better.

However, there was a sense of disappointment too, in that all the underlying activity was ultimately constrained by the need for it to be profitable in the current system. It was all predicated on growth, production and consumption.

That realisation was deflating. We had taken all these steps and then realised that we were still participating in the extractive financial system.

This led directly to the question of ‘what other models exist for holding capital for social justice work?’ and prompted an exploration of the idea of community capital stewardship.

The initial stage of this work was only fully implemented in 2021. Those involved saw it as getting the organisation to a much more congruent place and as a basis for further development and inquiry, including into other asset classes.

By this time, however, the wider organisational analysis had shifted to a fundamental critique of the whole system of capital accumulation and investment.

This underpinned the decision to redistribute Lankelly’s assets and close the organisation. Implicit in this was the sense that Lankelly didn’t see the potential to affect the kind of change we were seeking through the investment system.

There is a pathway for other foundations to go further down the track we were exploring.

We took steps based on a long-term time horizon which was shortened dramatically once the decision to fully redistribute was made.

People thought we were stepping in as a long-term partner and were excited by that, particularly as investment managers often feel they are stymied in taking a longer-term view by investors who are impatient for short term returns. Our choices around asset allocation were based on a long-term view and a corresponding attitude to things like volatility.

Affecting change through the investment system, as with any kind of systems change, is a long-term proposition. We should have realised that our actual appetite for a long-term commitment wasn’t certain.

Stopping and starting has been a feature of Lankelly throughout its later life, and it is also a philanthropic glitch in general. Foundations can and do change strategy without accountability.

Though our big strategic shift to redistribution meant it didn’t play out as an issue, we probably misjudged our governance capability and capacity. We selected a number of investment managers and intended to work closely with them. At this point (by design) we had an investment committee that held less technical expertise. We probably wouldn’t have been able to leverage the opportunity as much as we hoped.

We went down a route of working with independent consultants who were better able to support what we wanted to achieve.

We found Colin Melvin of Arkadiko Partners and Nicola Parker very helpful.

Resources

-

Charitable Endowments: The £68bn Elephants in the Room?

Dominic Burke

2020

- Investments

-

Transparency can Transform the Impact of our Investments

Dominic Burke

2021

- Investments

-

Investing Beyond the Growth Paradigm

Dominic Burke

2021

- Investments

-

How Should Charities Invest?

Dominic Burke

2021

- Investments

Related stories

-

Philanthropy’s future tied up with wealth inequality

Massive public policy agenda barely off the ground.

Jane Millar, University of Bath Read more -

Backing the country’s first community-led investment fund

I’d love to see philanthropy let go of the old ways and stop sitting on massive funds.

Cameron Bray, Barking & Dagenham… Read more -

Money needs to flow for all of us to survive

Navigating the foundation space.

Aliyah Hasinah, Black Curatorial Ltd Read more