Having coined the term ‘severe and multiple disadvantage’, we set about commissioning and funding a variety of research projects.

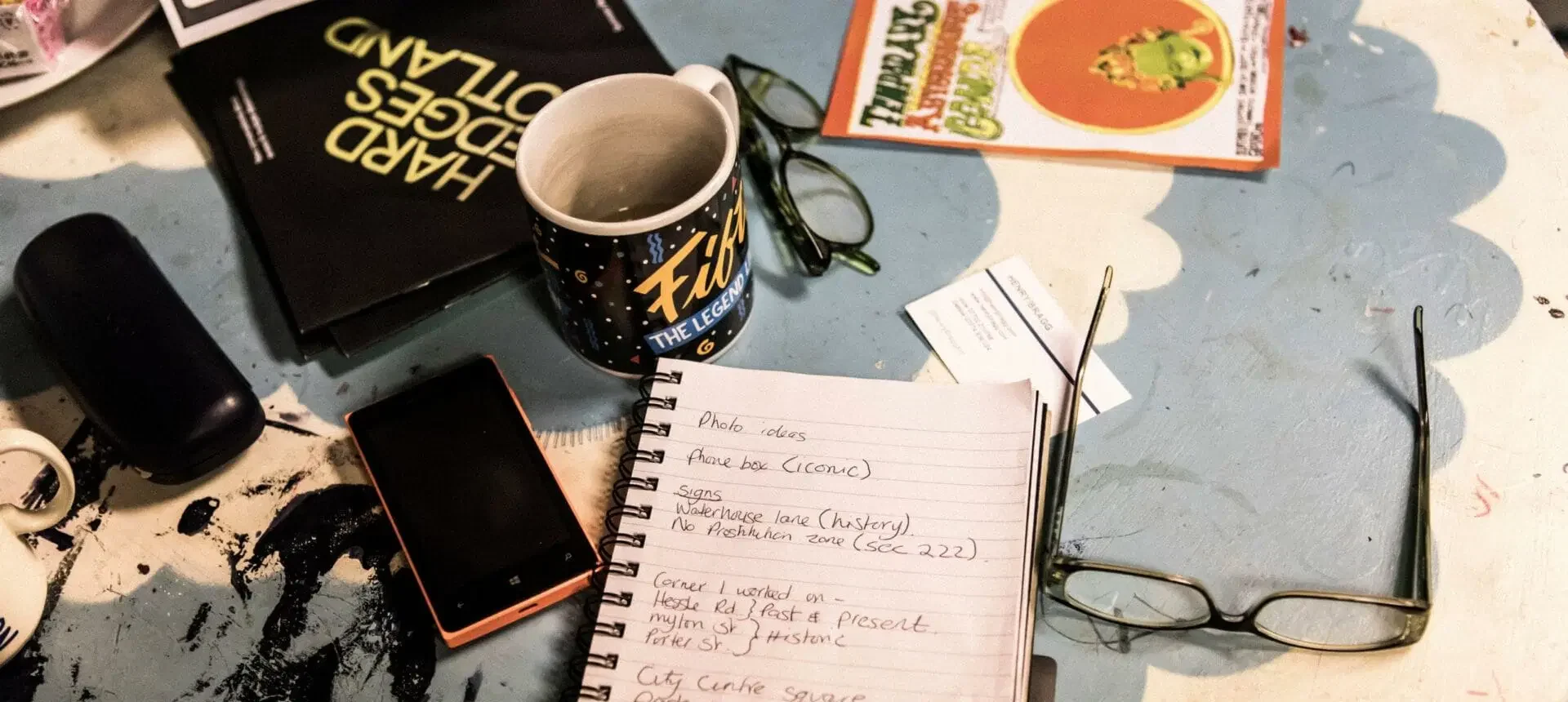

The intention was to illuminate the scale and nature of interconnected social harms. The most notable and influential piece of research from this phase was the Hard Edges report (2015), by academics at Heriot-Watt University.

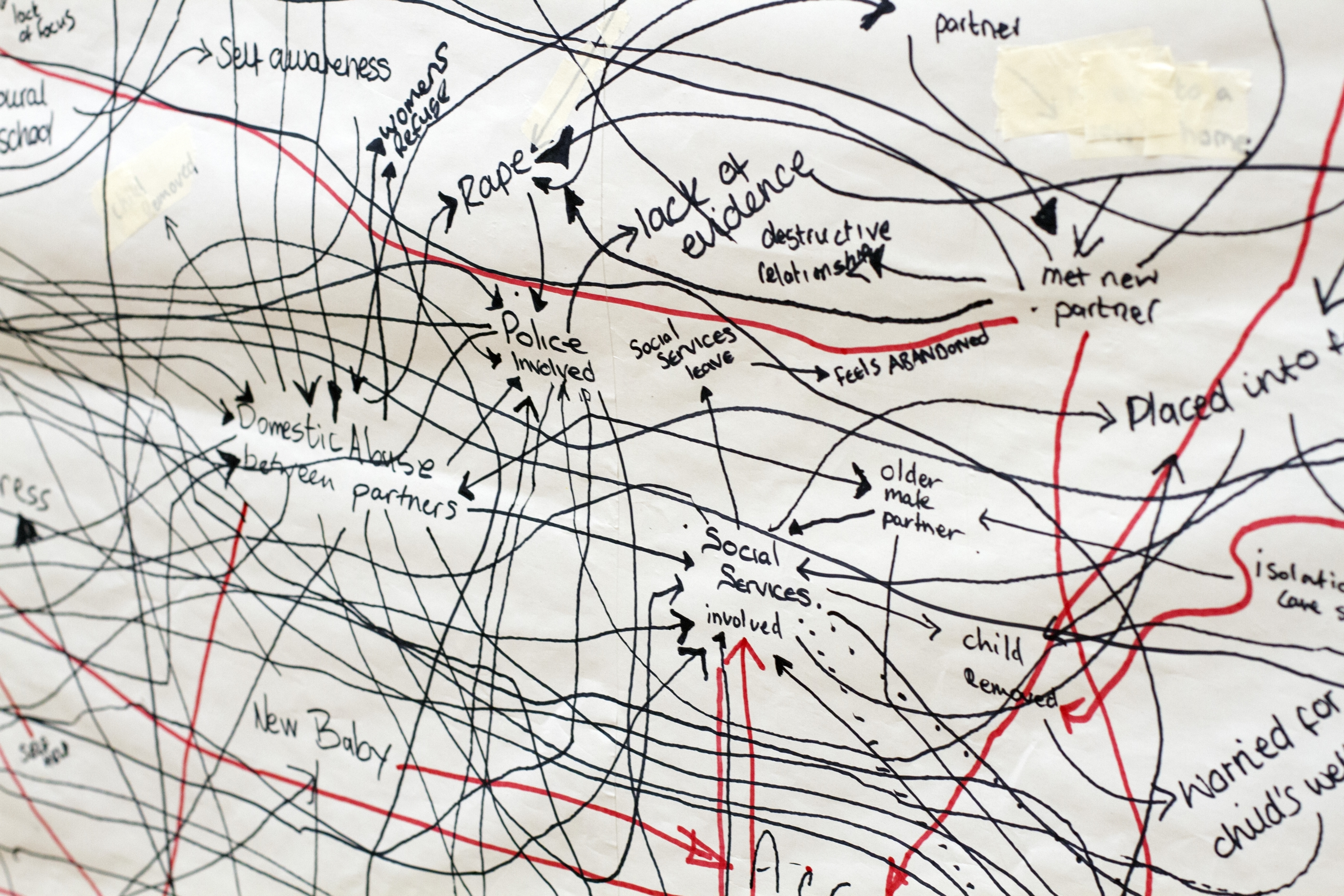

This concluded that there was a core group of 60,000 people who were simultaneously in contact with homelessness, drugs and alcohol, and criminal justice services.

Following Hard Edges, we also funded and commissioned a number of complementary research projects to explore different experiences and perspectives on similar issues.

This included ethnographic and storytelling approaches which focused more on the voices of people with lived experience of harm – ‘the lives behind the numbers’ – and studies focused on race, sexuality and gender inequalities.

We needed to learn more about the issues we wanted to address, and to illuminate the different experiences of people facing multiple disadvantage.

We knew that building the evidence based around our mission would support our own influencing work (as well as that of our partners making similar arguments) and open up conversations in the wider world, including in government and policy circles, where major decisions about the landscape of service delivery are made.

Hard Edges was an extremely influential piece of work, which really put ‘severe and multiple disadvantage’ and ‘multiple complex needs’ on the map of policymakers, commissioners and service providers.

It managed to highlight the interconnections of social harms to new audiences, whilst resonating strongly with those already familiar with its themes – particularly people working in support services, and people with lived experience of disadvantage.

It was impactful in making the core argument about siloed versus joined-up service provision, and its findings helped to inform a number of policy and practice initiatives including Making Every Adult Matter (MEAM), Fulfilling Lives, Changing Futures and Troubled Families.

Restrictive conceptions of ‘severe and multiple disadvantage’ became stuck: the boundaries of the debate around homelessness, the criminal justice system, addictions and (often) mental health became their own ‘hard edges’.

This created new exclusions, and ‘SMD’ became another damage-based label to attach to groups of people.

This troubled us, as we knew there were issues and people being missed by statistical and service-based data trawls in these domains, particularly women and people of colour.

We saw that new siloes were forming, and that the reasons for the inclusion or exclusion of particular people and groups from our work was becoming less and less coherent.

The debate could even become unpleasantly competitive, with different groups vying for consideration as the ‘most disadvantaged’ or the ‘biggest problem’. Our confidence that we’d drawn the right boundary(s) faded.

This is discussed in greater detail in the ‘knowledge’ section.

Our work was also used to support policy interventions we felt distinctly uncomfortable with – see this article from the Daily Mail.

Hard Edges in particular led to a purple patch of influence, and was at least partly responsible for significant expansion in policy and practice focus on multiplicity and interconnection, rather than individual siloes.

Because we were heavily involved in the report, it became part of our own ‘brand’ rather than just something that we’d funded; this enabled us to inhabit a more active and mission-driven identity, beyond ‘just a funder’.

The work on profiling disadvantage made it clear that our mission related to a ‘wicked’ or complex problem, i.e. it had a number of interdependent variables, many of which were uncertain and could result in multiple potential solutions, and which could not be solved through linear or predictable means. Accepting this changed our approach and led to our focus on systems change.

Resources

-

Severe and Multiple Disadvantage: A Review of Key Texts

Julian Corner, Mark Duncan

2012

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

Hard Edges Scotland

Suzanne Fitzpatrick et al

2019

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

People not Problems

Centre for Social Justice, Fabian Society

2019

- Public services,

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

What Have We Learned About the Lives of People Facing Severe and Multiple Disadvantage?

Cathy Stancer

2016

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

Hard Edges

Bramley, Fitzpatrick et al

2015

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

The Knot: Poverty, Trauma and Multiple Disadvantage

Various authors

2021

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

Related stories

-

When trust transforms the power of relationship driven narratives

Opening doors to hidden voices.

Jude Habib, Sounddelivery Media Read more -

Enhancing lives beyond traditional metrics

How Rob McCabe and Lankelly Chase pioneered relational support in Birmingham.

Birmingham Pathfinder Read more -

Address fundamental issues like power and wealth

A golden thread to make the scale of change we aspire to.

Chris Dabbs, Unlimited Potential Read more