Hard Edges gave us a certain profile of ‘severe and multiple disadvantage’.

The people it identified as simultaneously in homelessness, criminal justice and substance misuse services were largely white and male.

We knew it was unacceptable to leave it at that, so we commissioned work to explore the ways disadvantage and marginalisation could be understood and profiled in the lives of women and girls, recognising that this would be different to the Hard Edges cohort. Based on this conceptual work, we commissioned and published a series of reports on women and girls and multiple disadvantage.

We also worked with the Barrow Cadbury Trust and the Pilgrim Trust to set up Agenda, a new alliance-based campaign focused on women and girls at risk of ‘SMD’. This proactive (and contested) intervention in the field was based on an analysis that generic charities working on issues of multiple disadvantage failed to take a gendered approach, that charities working in the field of violence against women and girls struggled to include those with very ‘complex needs’ (in the language of the time), and that there was an unhelpful amount of funder attention on women in the criminal justice system (rather than ‘upstream’ work to prevent women being swept up in that system in the first place). Agenda was intended (by the funders) to occupy the space in-between.

The work on women and girls inevitably led us to ask who else we were missing. Our ‘jigsaw’ approach led to us funding and commissioning a whole series of reports on different experiences of severe and multiple disadvantage, with a focus on very hidden perspectives and communities.

These included children missing from education, young people, and Justlife‘s important work on the experiences of people in unsupported temporary accommodation.

Of course the jigsaw did not give us a complete picture as this is impossible – not least because experiences overlap and are dynamic.

The Hard Edges approach was certainly one legitimate way of defining ‘SMD’. Experiences of homelessness, substance misuse and criminal justice services did coalesce and reinforce each other, and the cohort was recognisable to people working in those services.

Organisations like Revolving Doors and MEAM were focused on this group, who were known to pinball around the system, trapped in cycles of crisis interventions.

However, this clearly wasn’t the only way extreme marginalisation played out in the UK. Lankelly had a history of funding charities working on issues around violence against women and girls, and also women in the criminal justice system.

Our knowledge of these fields, coupled with the absence of women from the Hard Edges group, led us to consider the limitations of our definition of ‘SMD’ and to seek to understand how extreme marginalisation played out in the lives of women and girls.

We ended up with quite the library of reports and studies on different groups of people. All were fascinating and illuminating and all have been used in different ways. We particularly valued those taking a participatory approach to get at very hidden experiences.

Agenda is an established part of the field and to the credit of the women who have led it, has proved its worth. In retrospect, it seems to us less a necessary strategic intervention by a group of concerned and knowledgeable funders (as it did at the time) and more an overstepping of the mark. It had the potential to destabilise the surrounding fields and to increase competition for scarce resources.

Getting into more conceptual debates about how disadvantage should be understood was an important step in our work.

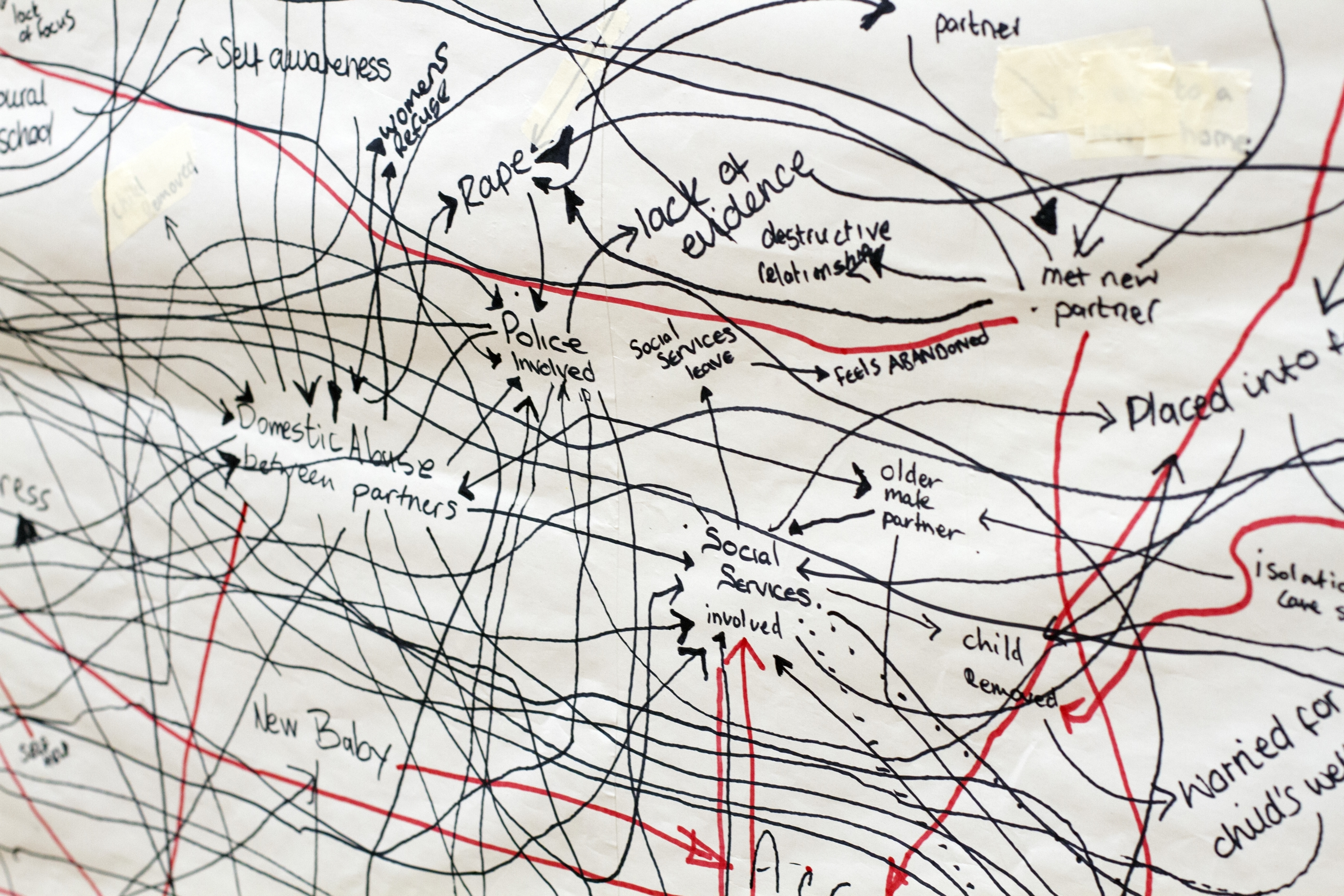

We recognised that the marginalisation of women and girls had particular dynamics that weren’t about their individualised ‘needs’ but were about patriarchy and oppression. This was integrated into our work and thinking.

We had been using a ‘defined categories’ approach for our research (using needs and/or presence in particular services as ‘qualifying’ criteria). We started to question this and to look at more expansive ways of understanding disadvantage.

The Capability Approach (the extent to which people are free to be and do the things that are important to them and live lives they value) and rights-based approaches seemed more appropriate. They did not stigmatise people, individualise them or neglect systemic oppression.

This line of inquiry developed into our work on ‘knowledge’, which began to question the fundamentals – our frames of reference, the things we take for granted; the ‘water we swim in’ without even realising it.

Resources

-

Gender Matters

Filip Sosenko et al

2020

- Severe and multiple disadvantage,

- Women and girls

-

Women and Girls at Risk: Evidence Across the Life-course

DMSS Research

2014

- Severe and multiple disadvantage,

- Women and girls

-

Women and Girls Facing Severe and Multiple Disadvantage

DMSS Research

2016

- Severe and multiple disadvantage,

- Women and girls

-

Lifting the Lid on Hidden Homelessness

Justlife

2018

- Homelessness,

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

What Have We Learned About the Lives of People Facing Severe and Multiple Disadvantage?

Cathy Stancer

2016

- Severe and multiple disadvantage

-

An Untold Story: Experiences of Life and Street Prostitution in Hull

Various authors

2018

- Severe and multiple disadvantage,

- Women and girls

Related stories

-

Develop longer term, more open partnerships

Allow grantees freedom to experiment and trust them to get on with it.

Katharine Sacks-Jones, Become Read more -

Lankelly empowered many people to challenge the status quo

That battle goes on—but now we’ve lost a valued advocate and vital resources too.

Sohan Sahota, BAC-IN Read more -

When trust transforms the power of relationship driven narratives

Opening doors to hidden voices.

Jude Habib, Sounddelivery Media Read more